“When you asked what love feels like, it’s so hard to explain,” she said. “But I could draw it—not anything specific, just colours.”

“And what are the colours of love?” I asked.

“A lot of bright orange, deep blue, and dark green.”

Ce qu'il y a de plus profond dans l'homme, c'est la peau. — Paul Valéry

“When you asked what love feels like, it’s so hard to explain,” she said. “But I could draw it—not anything specific, just colours.”

“And what are the colours of love?” I asked.

“A lot of bright orange, deep blue, and dark green.”

I wish I could share not just the transcript of my interview with Larissa, but also the story and details of how we met. Sadly, my memory of that day is almost entirely blank. I only remember two things: it was November 25, 2022, and the night before, I had been inconsolable. My most beloved companion, my cat Rick, had passed away that night at Tierspital in Zürich. Grief consumed me; I cried endlessly until morning. Somehow, I managed to gather myself just enough to get through the interview, but the rest of the day remains a haze.

“What matters most to you in life?”

“Spending time with people I love. It’s when I feel the most accepted, and it gives me the most energy.”

“And what does love mean to you?“

“Acceptance—if you want to break it down into one word,’ she paused. ‘I think you can’t really describe it.”

“Yet, we always try, don’t we?”

“Yeah. Some say it’s just a concept, others call it an emotion, or even a choice.”

“What’s your concept of love?”

“It’s the essence of living.”

“And why do you see it that way?”

“Like I said, it’s something shared between me and others that gives me energy. Can you imagine life without passion for something?”

“What are the things you’re passionate about?”

“I’m passionate about being with people and listening to their stories—like you do in your project, always connecting with new faces. I also love history. I’m half Swiss and half Brazilian, and I feel especially passionate about my Brazilian heritage. It’s funny, though—people don’t usually see that side of me.”

“What’s the difference between your Brazilian and Swiss sides?”

“As a Brazilian, I feel free to express my emotions openly, without holding back. In Switzerland, though, there’s a stricter sense of staying within a role. In Brazil, people say what they think—nothing is hidden.”

“Who or what do you appreciate most in your life?”

“My parents. They’re like angels to me—especially my dad. He’s not just my angel but also my soulmate. It’s incredible how much he understands me. No matter what happens in my life, I know their love for me is unconditional.”

“What is unconditional love?”

“Again, I think it’s about acceptance—accepting someone for who they truly are.”

“And who are you?”

“I’m a love giving, calm and dreamy.”

“What is your fondest dream?”

“To move—like a dance, to move through the world and feel the vastness of space. It brings me calmness and reconnects me to my true self, which I can then share with others. I’m studying artistry, and for me, museums are like vast spaces too. Just walking in a museum feels like home. My dream is to give this feeling to others—to show people the beauty and meaning in the small things. That’s what I want to do.”

“What kind of small things?”

“When people find out I study artistry, they often ask, ‘What are you going to do with that? Just look at Renaissance paintings?’ But it’s so much more than that. Yes, we study Renaissance paintings, but it’s really about the people who created them—their stories, their why. I believe we’re all creative beings, but many of us have buried that creativity deep inside. I want to help bring it back, to share the calmness and joy of creating, and to remind people what it feels like to be truly creative.”

“So, what are the small things you pay attention to?”

“It can be anything. For example, how this room is constructed. Or take that picture on the wall—someone might glance at it and think, ‘It’s not my thing.’ But if you take the time to look closer, to really see it, something flat and two-dimensional might open up, revealing layers of meaning. You’d realize everything is connected within the space. I remember once standing in front of a simple landscape painting, and for a moment, it felt like my soul left my body, breathing freely, suspended in nowhere. That’s how profound small things can be.”

“This brings us to the question of the beauty of big things.”

“And how would you define big things?”

“Through the lens of small things. So let’s start there.”

“Small things are the ones most people overlook, the ones they take for granted. They’re so small, they almost go unseen.”

“And how do you define beauty?”

“Beauty is something that touches you deeply.”

“How would you like to be remembered?”

“As a caring person who gave a voice to things that often go unnoticed or unappreciated. When I was a child, for example, I felt that the color orange didn’t get enough love. People would always say they liked blue or red, but rarely orange. That made me sad, so I decided to give orange my attention and tell everyone, ‘Orange is fine and cool too!’ And once I did, I started noticing orange everywhere.

It’s the same for me with insects. Most people are disgusted by them, wanting to kill them or keep them away. But have you ever really looked at a bug?”

“Honestly, it took me a while to get along with insects. I was never really exposed to them before, so when I moved into the house in the forest, my first instinct was fear—that they could hurt me, maybe even kill me. But then I realized that’s true of almost anything in life. Once I understood that, I started to see them differently, almost like befriending them. I began to appreciate their umwelt—their unique little world. It became like saying, ‘Hey there, little one, I see you’re scared of me, but don’t worry. I won’t hurt you. You do your thing, and I’ll do mine.“

“I’ve also come to really respect them. Last year, I did a project about insects, and everyone kept asking, ‘Why insects? Why would you focus on that?’ I’d tell them, ‘Because I find them fascinating and beautiful—not just butterflies, but all bugs!’ Most people thought I was a bit of a weirdo for it. But over time, some of them started to change their minds. Now, they’ll occasionally come up to me and say, ‘Larissa, thanks to you, I see them differently too.’ And that means a lot to me.”

“What do you believe in?”

“I was raised Catholic, but I’m not religious. I believe we’re all connected, one with the universe. At first, my mother was very concerned—it’s a big deal for my parents. But it turned into something sweet. One day, she came to me and said, ‘You don’t have to be Christian, but what’s really important to me is that you have fé.’ It’s a Portuguese word, and I wish I could find the perfect translation. It’s like hope, but deeper—more profound. She told me, ‘If you have fé in your life, you can face anything. You just need this to keep going.’”

“If it’s hope, then hope for what?”

“For everything.”

“What morals and ethics govern your behavior?”

“I try my best not to harm any living being. That principle often leads to debates with entomologists who kill insects for preparation. I tell them they don’t need to take a life just because it’s easier. I also find myself explaining to people why I don’t consume meat or dairy—it’s part of the same commitment to minimizing harm.”

“What is the most important lesson life has taught you?”

“That I’m incredibly privileged, and it’s my responsibility to use that privilege to do good.”

“How do you feel?”

“The ambiguity of my current state affects my well-being, but I just returned from my summer holiday, and I feel very optimistic—ready for new challenges. I’m also excited about this session. It’s not something I do every day.”

“Could you describe that feeling of excitement?”

“It’s joyful. I’d even call it an addiction—but a positive one. It motivates me to explore new things. Except… hmm, no, that’s it.”

“Do you see any downsides to this addiction?”

“Well, yes. It can distract me from my long-term goals, like staying true to myself, keeping my family happy, and having a satisfying sex life. But honestly, it’s hard to give up those short-term pleasures, especially when they’re just within reach.”

“Let’s start with staying true to yourself. What does that mean to you?”

“To stay free.”

“Is that difficult?”

“For example, my fiancée and I are getting older, and I struggle with how to feel desired by her. After she gave birth to our child, my sexual needs…” He paused, searching for the right words.

“…are not being met?” I offered.

“Yeah, they were not and still are not. And for you—what does being true to yourself mean?”

“For me, it’s about taking care of my health.”

“What brought that on?”

“Maybe I’ve become more aware of how my body feels. Plus, like you, I have long-term goals, and I realized I need to stay fit and resilient to achieve them.”

“Makes sense.”

“What are the sexual needs that are not being met?”

“I’m quite active—or at least I would be if I had the opportunity. On one hand, I want to stay loyal. On the other, I feel like I need more. And I don’t want to hide that need.”

“What is this need about?”

“I just want to have more sex.”

“And how do you cope with the lack of it?”

“I’ve been seeing a therapist—he’s my age—and he suggested a few possible solutions. First, I could wait and hope it resolves itself, but he advised against that. Second, I could meet other women covertly and just fuck them. Third, I could talk to my fiancée about an open relationship. Fourth, I could discuss our needs together, stay loyal, and maybe even try couples therapy. Fifth, I could learn to feel okay with less sex—which I’ve already been working on. Honestly, I’ve noticed some upsides, like having more testosterone that makes me better at sports. And the last option? Breaking up.”

“Are you leaning toward any particular option?”

“Probably the fourth—working together on our needs and finding a compromise. But it’s not easy, I have to admit.”

“What is your biggest dream?”

“To be honest, I’m quite satisfied with my life right now. I have good health, a wonderful son, great friends, supportive parents, siblings, and a good job. I don’t feel the need for a big dream.”

“Have you read The Unbearable Lightness of Being?”

“Yes, it’s actually one of my favorites.”

“Then you must remember Sabina, whose drama was not one of heaviness but of lightness.”

“Yes, I do. But I’ve always struggled to fully understand the story of Tomáš and Tereza. He had affairs with so many women, yet it didn’t destroy their relationship. When you consider the vastness of the world and the entirety of history, a single moment in a love affair seems insignificant. Does that mean someone can live like Tomáš? Maybe not. Ethics and morality come into play. People are fragile, and over time, they can falter. I still have doubts about it.”

“What are your ethics and morality?”

“Beyond the obvious ones, the first thing that comes to mind is avoiding harm or trauma to others—not just physically, but also psychologically.”

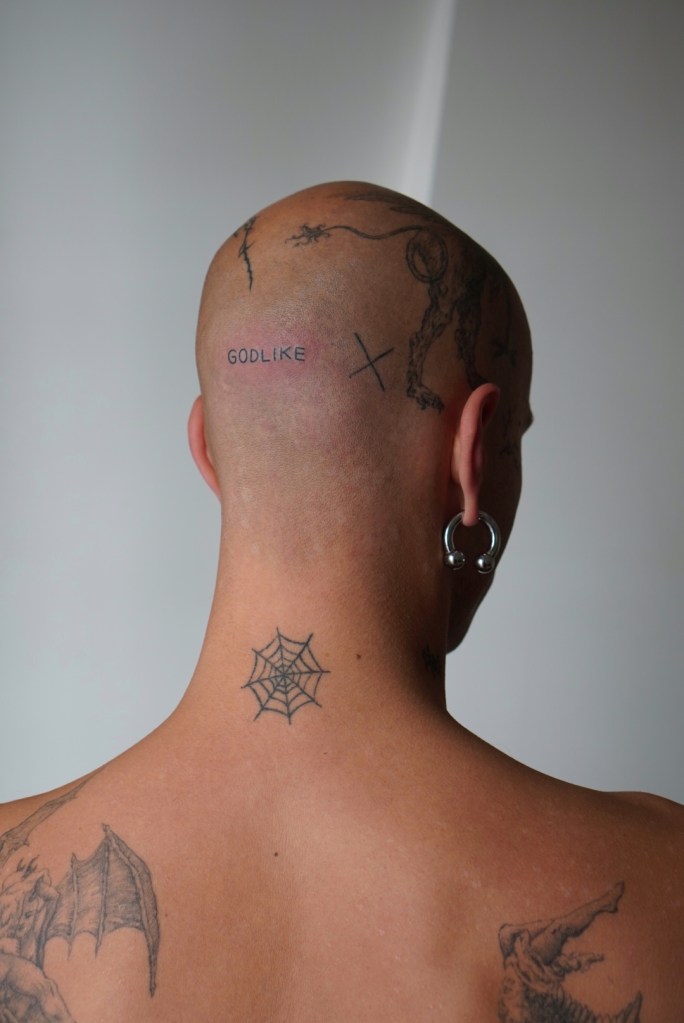

“How do you feel about the idea of tattooing ‘One day without harming you’? It’s the title of a musical composition, but to me, it holds the wisdom of humility. Some days, you unintentionally hurt others, and on other days, you don’t.”

“That’s deep. But the word ‘harm’ brings up a negative emotion—it makes me think about harming. Do you have other ideas?”

“Yes, ‘Practical Arrangement.’”

“How do you interpret that?”

“It came to mind when you mentioned working with your fiancée to address your needs and find a compromise. It feels like a balance between effort and understanding.”

“Interesting.”

“It’s also the title of a Sting song. He wrote it after years of marriage.”

“How did they end up?”

“They’re still together.”

“Can I write down your ideas and think about them?”

“Of course!”

“I’m not sure I want something as clear as ‘Practical Arrangement.’”

“Well, without the context, it’s not so clear.”

“Yeah, you’re right. Let’s stick with it. Do you think you could depict this as a drawing?”

“No, that’s outside my expertise.”

“Okay, ‘Practical Approach’ then.”

“Arrangement.”

“Fuck! Practical Arrangement. Hmm. Which of the ideas do you prefer?”

“The first one. It feels more emotional and touches the heart, while the second one speaks more to the mind.”

“Oph-ph-ph. We’ve got time, right?”

“Yes.”

“Maybe we can talk a bit more?”

“Sure. What is it you miss most about having sex?”

“Excitement and pleasure.”

“Can you elaborate? Where does the excitement come from? Is it tied to the pleasure of penetration?”

“Ahh, okay! I t h i n k , w h a t I , m i s s m o s t i s t h e f e e l i n g o f being desired.”

“Desired. How does that word make you feel?”

“It’s a struggle.”

“I mean, as a tattoo. It’s provocative, sexy, and emotional.”

“Yeah, that’s a strong one!”

How did you realize fashion was your passion?

My parents exposed me to culture at a very young age, and my father has always been deeply sensitive to anything related to beauty. He began, his voice warm and deliberate, prolonging his words with a soft smile. My first real encounter with fashion was when I met Karl Lagerfeld in the south of France. He inspired me, not just in terms of aesthetics but in building a strong, globally recognized persona. The fact that Lagerfeld acknowledged me, talked to me—it gave me confidence. That’s when my passion for fashion truly started.

What is beauty to you?

It’s anything that provokes a joyful reaction in my body.

Describe yourself in a few words.

Intense! That’s it. It says everything. I live at a hundred percent—I party hard, work hard, fuck super hard. But I always stay in control. If I want to stop, I stop. If I want to quit, I quit.

How do you maintain control?

I value myself. If something doesn’t feel right, I don’t do it. That can be a problem at work, which is why I’m a freelancer. I can’t have someone telling me what to do because, honestly, I think everyone is wrong but me. (laughing)

And what about the things you can’t control—like other people?

Oh, but I can. When I started in Paris, I went to fashion parties to meet the people I wanted to know. It was so easy. I’d walk up to them and say, ‘Oh my god, hi, how are you? I haven’t seen you in so long!’ Everyone’s polite, so they’d respond, ‘Oh, hi, how are you?’ pretending they knew me. By the next time we met, they actually thought they did. And that’s how I got to know them.

What else can you control?

I completely control how I look. Only I decide how to change myself, and I don’t adapt to my surroundings. That’s how I stay true to myself. And because I’m happy with who I am, I have the power to get and control whatever I want.

What do you appreciate most about yourself?

The way I provoke people. They either love me or hate me—never indifferent. I love dressing to turn heads.

Why do you want that attention?

Maybe because I was adopted. But I don’t feel the need to find my birth parents—I’ve been given an incredible life. Still, being abandoned might have left its mark. And growing up, my father worked at the European Central Bank, so there were lots of ‘show-off’ situations at school. I always felt the need to prove I was different, maybe even better than everyone else. (laughing)

What makes you different?

I’m different because I say I’m different. Whether it’s true or not, I pretend harder than anyone else.

Is there anything you dislike about yourself?

My lack of self-control when it comes to pleasing myself. If I want something—even if I can’t afford it—I’ll find a way to get it.

What’s your guilty pleasure?

Seduction.

Why does that make you feel guilty?

Actually, it doesn’t. (laughing) Okay, then—doing drugs.

When was the last time you felt truly happy?

Every time I’m with my boyfriend.

What does love mean to you?

An endless cycle of giving, taking, and exchanging.

Why is it endless?

Because I don’t want it to end!

What’s your dream?

To be the most successful in my field.

What do you believe in?

Myself.

What was your dream ten years ago?

To be famous.

What does fame mean to you?

To be respected by people.

And how many people do you need for that?

Only those I respect. They’re the ones who matter.

What’s the most extraordinary thing you’ve done?

I styled the Met Gala—that was huge. And I worked on the Cannes Festival too.

How would you like to be remembered?

As someone who changed something.

“Do you consider yourself a free person?” I asked.

“No,” she said. “I grew up constantly trying to be the best version of myself—to make my parents proud, to have friends, to catch the attention of boys I liked. It was always about improving myself. But eventually, it became exhausting, trying to live up to this ideal version of me that I imagined. For instance, I have a vision of a perfect me, but I don’t look like that.”

“Describe this perfect image,” I prompted.

“It would be a thinner me, taller, with a different nose. Someone always polite and joyful, working hard, successful, stylish, with a rich social life, liked by everyone, and having a lover.”

“And how do you see yourself now?”

“I usually describe myself in terms of what I lack. But I guess I can be funny sometimes—it helps me feel more confident with people. Mostly, though, I’m sad. I’m a very loyal friend, but I’m also difficult—too dramatic, always tired, often depressed.”

“How do you feel right now?”

“Honest. I always want to be honest, but my exhaustion comes from holding everything in. I don’t want to say things that might hurt or disappoint others. For example, with my parents—I have no reason to feel sad. They’re happy together, I’m healthy, I have a roof over my head, and a job.”

“If you don’t want to feel sad, how do you want to feel?”

“I want to feel happy.”

“What does happiness mean to you?”

“Being at peace. Waking up in the morning feeling light, like good things are coming, and being excited about them.”

“But what if the good things come with bad things? Life is never just one or the other, right?”

“The problem is I feel more of the bad than the good. This ideal version of myself, not living up to it, makes me feel like a failure. It makes it hard to enjoy the little good things in life.”

“Have you ever been in a place or moment where you wanted to be?”

“Yes, but I don’t know how to appreciate those moments. I always think I should be doing better.”

“You said happiness is about being at peace, which isn’t about being better or worse than someone, but welcoming whatever comes—whether it’s sadness or joy. Like Buddhists say, nothing truly belongs to us; emotions come and go like clouds in the sky.”

“I struggle with letting go. Especially with the fact that people come and go. I don’t know how to cope with the feeling of being left behind. I keep thinking I need to get them back. I don’t feel whole without the people I love.”

“What does love mean to you?”

“It’s something I crave. I think I have too much love to give, and that scares people because I ask for a lot of love in return.”

“What exactly do you give to others?”

“Attention, time, affection, support—just being there for them.”

“And if they say, ‘We love you, but we need space right now’?”

“I understand that. I sometimes need to be alone too. But I have so many feelings, I don’t know how to keep them to myself.”

“Do you think someone with fewer feelings might want to take some of yours?”

She laughed. “Maybe. I just don’t know what to do when people want to be alone.”

“Maybe you’re seeking help, not love.”

“But I am getting help—I see my therapist twice a week,” she laughed again.

“I only said that because love, in my opinion, isn’t about expecting something in return.”

“Yeah.”

“So when people leave, it’s something they need. Loving them means wishing them well.”

“I do wish them well, but it makes me incredibly sad when what’s best for them is being without me. It hurts—so much. I don’t want to force them to stay, so I say, ‘Of course, do whatever you need.’ But I don’t say what I really feel. I’m afraid they’ll feel trapped if I do.”

“It’s not really our responsibility how others feel. For instance, you could say something to me now, and it might not hurt me. But the same words, on a different day, might sting because of my mood. It’s up to me how I react—or don’t react.”

“I’m an empath,” she said, tears welling up. “I just don’t want to hurt people. I try so hard, but I’m human. I make mistakes, and that’s hard to accept.”

“What if there’s no choice but to accept it?”

“I know! That’s the thing,” she smiled through her tears. “I know that!”

“It’s like there’s a wall and a door in front of you. You know there’s a door, but you keep staring at the wall.”

She laughed. “Part of me gets it, but the other part is irrational. That part overwhelms me with guilt.”

“Here’s something that helps me: instead of resisting overwhelming feelings, try to notice them. Name them—‘Okay, guilt is here.’ Then, open yourself to the feeling and investigate it. How does it feel in your body? When you stop resisting, other feelings can flow in. It’s about practicing a laid-back curiosity toward what you feel.”

“I’d like to try, but I don’t know how.”

“I wish I could give you my experience, but you have to see it for yourself.”

“I don’t know where to start.”

“Start by paying attention to sensations—what you see, hear, smell. It creates a little distance between you and your thoughts.”

“My therapist gave me the same exercise for anxiety. But when I’m anxious, it takes over. I can’t eat, can’t sleep. The exercise works for five minutes, then the anxiety comes back.”

“Even a second of relief is worth it. Those little breaks add up.”

“I try, but the last year and a half, I’ve been falling apart. Crying, sleeping, living in a mess. I had no energy to tidy up.”

“What happened a year and a half ago?”

‘It was a teeny tiny thing, but it was too much. I used to have a lot of piercings, but a year and a half ago I got an infection. I went to see a doctor, and he gave me a cream with antibiotics, but it didn’t work. It was a small infection. I went to see another doctor, and he gave me antibiotic pills, but it didn’t work. I was taking more and more antibiotics, but my body didn’t respond to the treatment. The other doctor said, if antibiotics don’t work, you have to do some tests. This is when my anxiety appeared. My piercings were the things that I liked about myself, making me more comfortable in my body, so this health issue felt really personal. It wasn’t getting any better, so I went to the hospital again, and I was asked to take all my piercings off. So, I had to take them all off, but only after eight months infection has cleared. I know, people find it silly that it was so hard for me, but for me it was more than just jewels, it was my body image. I started crying at work, telling people I’m unwell, I’m sad. It felt like I became a burden for my loved ones.’

She wore a bracelet, three rings, two necklaces and six earrings: all in gold.

“How do you feel?” I asked her.

“I’m excited to talk with you,” she said with a laugh. “And there’s your dog! I’m always happy when I see a dog.”

“What does happiness mean to you?”

“It’s that feeling when you don’t need or want anything more than what you already have. When I’m happy, I can’t help but smile all the time,” she said, laughing again.

“Is there something in your life that makes you unhappy?”

“A lot of things. Mostly, people. Crowds of people. When I’m in the metro or walking on the street, I get defensive and feel uneasy.”

“What is it about the crowd that makes you feel that way?”

“It’s like everyone is watching me, even though no one actually cares. I just blend in, and it makes me feel disconnected—like there’s no genuine contact with anyone.”

“And why does that unease you?”

“I just don’t like people in general. I prefer animals. With people, I find myself disagreeing on so many things.”

“You say you don’t like people, but you’re also one of us, aren’t you?”

“Yeah.”

“Does that mean you dislike yourself as well?”

“Yeah.”

“Describe yourself.”

“I’m a very giving person. Even though I don’t like people, I work as a nurse in a hospital. But when I say I don’t like people, I mean the crowd. Crowds dehumanize you. They strip away your uniqueness.”

“What’s your uniqueness?”

“Everyone has their own uniqueness because everyone is different. It’s the comparison with others that makes us unique.”

“What is it that you give to others?”

“My time, my attention, and gifts.”

“Why do you do that?”

“It makes me feel like I matter, like I’m seen and important.”

“And why do you need that?”

“I suppose it’s because I don’t really feel important. With my mum, I feel too important—she’s always watching me. My dad, on the other hand, is more of an absent figure. From the age of twelve, I started to strongly dislike myself. Even though it’s a bit better now, I still struggle with it. Giving gifts to my friends gives me a sense of purpose in life.

But it’s strange—sometimes I want to be seen, and other times, I just want to disappear.”

“What matters most to you in life?”

“Not much, really. Maybe just to feel happy. If you’re not happy, what’s the point of living?”

“But we can’t always feel happy.”

“Oh, of course, I mean being happy overall.”

“And what if someone doesn’t feel happy overall?”

“Then they need to change something.”

“Is it so bad to feel unhappy?”

“I don’t know, honestly. When I’m unhappy, I don’t want to do anything. And life is long—if I spend sixty years doing nothing, that would really suck.”

“What do you mean when you say life is long?”

“Sixty or eighty years feels like a long time. Sure, time flies, but when I think about it, there’s so much time to do whatever you want. Maybe not everything in one day, but in a year? That feels possible.”

“Time is just a concept, in my opinion. But cultivating the thought that we might die at any moment can be incredibly important.”

“That’s the thing—everything has an opposite. Like, I know myself, but I don’t really know myself. Life is long, but life is also short. That’s why I’m so confused,” she laughed. “Before this conversation, I thought I knew myself better.”

“Is there something else you have doubts about?”

“I’m not sure if nursing is right for me. I try not to think about it, because when I do, it paralyzes me with anxiety. Sometimes I wonder if I should stay in the hospital or explore veterinary medicine instead.”

“Usually, it’s not the doubt itself that causes anxiety but the inaction. The answer is probably already in your heart.”

“Yeah, I know I don’t want to be a nurse forever.”

“Does the idea that life is long hold you back from acting?”

She laughed. “I don’t know. If life is short, then I don’t know what to do with it. Should I change everything or just try to be happy with what I already have?” Her eyes filled with tears.

“You are a teacher of mindfulness and assist people in equitherapy. Let’s start with mindfulness—what is it?” I asked her.

“It’s a state of being present—in your thoughts, feelings, and environment. It’s about learning to observe without judgment and embracing the present moment instead of dwelling on the past or worrying about the future.”

“Is there a connection between mindfulness and equitherapy?”

“Yes. Horses are naturally present; they live entirely in the moment. I believe they embody mindfulness.”

“Let’s imagine I’m your patient. We meet at an equestrian facility—what happens next?”

“Our first meeting would be about getting to know each other. I’d usually ask, ‘What’s your intention?’”

“And what’s the most common intention your patients have?”

“Most of them come because they lack confidence.”

“Alright, let’s say my intention is to gain self-confidence. What happens next?”

“The next step is finding a horse to partner with you in therapy. Once you’ve chosen your horse, I’d give you a task. It might involve caring for the horse, guiding it to move in a certain way, riding, or even just walking with it.”

“Is there something you feel is missing in your life?”

“Lately, I’ve been missing having a life partner.”

“Why do you feel you need a partner?”

“I’ve never really thought about it, so I don’t know why. Maybe it’s because I want to build a family home, to feel secure.” Her voice trembled, and she began to cry.

I handed her a handkerchief. “Do you feel insecure now?”

“No.”

“Then maybe you don’t need a partner to feel secure.”

“Yes, but sometimes I do.”

“Do you think having a partner would make you feel secure all the time?”

“I’m not sure,” she said with a small smile.

“I don’t want to live my life alone,” she cried again.

“Would it be fair to say that you want a partner to escape aloneness?”

“Maybe… maybe just to soften it.” Her tears slowed.

“May I ask what was on your mind while you were crying?”

“Security,” she said, tears welling up again. “But it’s not sadness. In recent years, I’ve realized how grateful I am for my family. These are tears of gratitude.”

“How do you feel?” I asked her.

“Excited!” she replied.

“Could you describe this feeling?”

“I feel it in my gut. It makes me happy and makes me smile. But it also brings a little nervousness about the unknown.”

“What does happiness mean to you?”

“Being at peace with yourself and truly accepting your life situation.”

“Is there something you feel is missing in your life?”

“Yes, peace with myself. I struggle a lot mentally.”

“What are those struggles?”

“I have depression and anxiety… and I used to be anorexic.”

“Would it be fair to say that you don’t accept your depression and anxiety?”

“That’s a good question. I’m not sure. They’ve been part of me for so long. Even though I don’t want them to define me, they still feel like a part of who I am.”

“How do depression and anxiety define you?”

“Sometimes I let them make decisions for me. Like not leaving the house, avoiding people, and sticking to familiar comforts.”

“Yet, you left your comfort zone to come here. And it’s you who is sitting here now, right?”

“Yeah, I guess so. But I think it’s because I don’t really know who Elena is. It feels easier to identify with something I do know—like anxiety and depression.”

“Do you feel depressed and anxious at the moment?”

“Yes.”

“Could you describe it?”

“Depression feels like a hole, an abyss—like hopelessness.”

“Could an abyss or hopelessness ever feel peaceful?”

“It could, in a way. But it becomes unsatisfactory when there’s too much of it.”

“What does ‘too much’ mean?”

“When the abyss is all there is, and I become just a body that breathes.”

“And what’s unsatisfactory about that?”

“Hmm… I guess it’s because I want some grounding in reality—like being financially independent from my parents. I want to accomplish things, to enjoy life, and not just exist as a breathing body.”

“Why do you want to be independent from your parents?”

“Because then I’d feel like my decisions aren’t tethered to them.”

“May I offer the perspective of being grateful for that tether while it lasts?”

“But they want me to be untethered because they can’t support me forever.”

“All the more reason to enjoy it while it lasts.”

“I want to, I really do. But there’s this voice in my head saying, ‘It’s going to be over soon, you need to figure it out.’ I agree with you, but it’s hard for me to silence that voice and just enjoy the moment.”

“Is there something else you can’t accept?”

“In myself or in the world?”

“I see no difference. Do you feel separate from the world?”

“Yes, I do. I often feel like I don’t fit in, like I don’t belong to any community. I have my family, but part of me wants to find a community outside of them.”

“What would make that different from having a family?”

“It would be something I find for myself, because I didn’t choose my family.”

“When you say ‘myself,’ it sounds like you know what that is. But earlier, you said you don’t know who Elena is.”

“You’re right. Maybe that’s exactly why I can’t find a community.”

“And what if I tell you it’s impossible to find yourself, because there is no self?”

She laughed. “I don’t know. Thinking about it now, maybe there really is no such thing.”

“I like the idea that the self isn’t a noun, but a verb—always changing. It means we can never fully figure ourselves out.”

“Then the question is, can I accept that I’m always changing? I think that’s where I struggle. I’m obsessed with finding something to hold on to, something stable, and I can’t seem to accept that I’ll never find it.”

“Why is it so important for you to hold on to something unchanging?”

“Because it feels comforting. Safe.”

“And yet, change is the only constant in life.”

“I know. But we still need something—benchmarks, relationships, something to hold on to.”

“Sometimes we feel like we have no friends, and other times we feel we do. We can feel connected or disconnected from the world, but it often comes down to perspective, to attitude.”

“I don’t think it’s that simple. For me, something has to actually happen for those feelings to shift. Feelings aren’t just in our minds—they have a physicality to them.”

“You mean you have to experience something to truly understand it?”

“Yeah, exactly. That’s why the body is so fascinating. Without it, we’d just be souls without any physical experience.”

“The feeling of separateness often comes from the idea that we’re imprisoned in our bodies. But when I realized that my body isn’t a cage—that it’s in constant conversation with the environment—I stopped feeling so separate.”

“I see what you mean, but for me, just accepting that I’m connected to the world in a non-bodily way doesn’t feel fulfilling. Maybe it’s because I was raised in the US, in such an individualistic culture. It’s always about me, me, me—not about becoming one with nature. That doesn’t mean I have to live that way, but I’ve been influenced by it. Maybe that’s why I’m still searching for myself.”

“What does connectedness mean to you?”

“For me, it has to be personal, intimate—not just with a crowd, but with people. That’s not to discount nature. I deeply value it, and I think we do a terrible job of appreciating it. But for me, nature isn’t above or more important than humans.”

“I’d suggest that perhaps you’ve underestimated nature. We breathe far more often than we communicate with people. The plants around you inhale the air you exhale, and you inhale the air they exhale. Without plants and their oxygen-producing abilities, life on Earth as we know it wouldn’t exist.”

“We could live in harmony with nature, but plants can’t talk to me.”

“Well, they do talk—but not in English. Do you know this plant?” I reached for a shameplant on the shelf and placed it in front of her.

“No, I don’t think I do.”

“Touch its leaves gently.”

She touched the leaves, and they folded and drooped. “Oh, it closes up, like an oyster. That’s so beautiful!” The leaves slowly reopened.

I don’t like when things change, even if it can be for the better. I like things to always be in order, she said to me.

Change is inevitable, isn’t it?

I know, I know. It’s very complicated for me.

Are you afraid to die?

Yes, I’m very afraid that my life could stop. I simply don’t want to die, although I have health problems. I try to cope with my disease by pretending it’s not there.

If you could live forever, what would you do?

I’m curious about many things. I want to know everything about everything. It drives me.

Why do you want things to always be in order?

This is something I can’t not do. I’m autistic, and that’s a way for me to cope with the chaos in life. When things are not organized, I feel sick.

Have you ever had a moment when everything was set in place?

Yes, in our flat in Ville d’Avray.

And what happened next?

My boyfriend and I, and our cat, we moved from this place to Rennes. It was too small for us. We lived there for eight years.

How is it in your new place?

I feel very good inside. Lately, it has rained a lot, so it was twice as nice.

The rain in Rennes. Would you like a glass of water?

Yes, thank you!

She was looking for something in her backpack when I returned with two glasses of water.

Sorry, I have to take a pill. I forgot about it. Actually, I have a big problem; I developed long COVID.

You mean you still have post-COVID effects?

Yes, it never stopped, so it’s quite complicated for me.

What are the symptoms?

I find it very hard to breathe. If I, for instance, have walked too much or just up stairs; every movement I do makes me need medicine to recover. I know that coming here from Rennes will cost me hours of breathlessness afterwards. I also have a problem with my memory. I can’t read anymore because I don’t understand what I read. My hands are trembling all the time. Sorry, what was the question?

You were sharing with me the symptoms of your long COVID.

When I change my body position, I feel dizzy and I could collapse. She found the pill and swallowed it with water.

How does your pill work?

It stops dizziness by raising my blood pressure.

Why is only one of your nails red?

I forgot to wash it off. I wanted to try red color, but I wasn’t happy with it, so I didn’t paint the other nails.

Thank you! Here is my idea for your tattoo. I handed her my notebook.

“Shall we?” Pierre gestured towards the entrance of Saint-Sulpice. Inside, he pointed to the first side-chapel on the right, and we sat before the mural of Jacob Wrestling with the Angel.

“What do you think?” I asked.

“Jacob will lose,” he replied. Then, after a pause, “Are you hungry?”

“No, I’m fine, but I’ll follow you.”

We found a table at Café de la Mairie. “Un quart de vin rouge,” he said to the waitress. He swirled the glass thoughtfully. “I haven’t been out in ages, but I think it’s not good for me. My brain needs air; otherwise, it spoils.” He spoke so softly I had to lean in to catch his words.

“Are you still hopeless about having children?” I asked.

He pouted slightly before answering. “The last woman I slept with didn’t warm me. She talked too much, nonstop, and at some point, she called me a silent man. I wouldn’t be silent if she ever listened to me. What about your cooking lady?”

“She wanted to own my heart, but you know, it was already broken. What was left, I gave to M. I told her I have nothing left but love for everyone, but she wanted more. So, she left me.”

“I’m sorry,” he said, glancing at his empty glass. “There’s no good food here, and I’m starving. Thai or Korean?”

“Korean. And let me pay for the wine this time.”

“Alright, but I’ll cover the Korean, and you can tattoo me a line tomorrow. Deal?”

“Deal.”

The next day, Pierre called. “I’m on the terrace of the brasserie called Ernest.”

“I’ll be there in a few minutes.”

He was seated in the sun, smoking a cigarette.

“It’s very bourgeois of you to drink wine at noon,” I teased.

“Why not? Care to join me?”

“No, thank you.”

The waitress brought him a small plate of couscous with falafel and diced tomatoes.

“Vous avez choisi?” she asked me.

“Rien pour moi, merci.”

Pierre winced after a bite. “It costs 14 euros and tastes like nothing.”

“Better tasteless than unpalatable,” I said, closing my eyes briefly.

“Let’s go,” he said, snapping me back.

We crossed the street towards La Place de Catalogne.

“I don’t like this Italian fascist architecture,” he said. “It all feels fake.”

“The architect is Riccardo Bofill. He was Spanish, and his work is considered some of the most impressive of the 20th century.”

“Logical, then. Catalonia is in Spain.”

At my place, Pierre stepped onto the balcony for another cigarette.

“Did you sleep well last night?” I asked.

“I woke up at three. Thought I had plenty of time before the day began, so I let myself be lazy and watched WWII videos. Here’s the line I want.”

He showed me a picture of his back with a new line sketched using an app.

“I’m not sure what to do with this triangle,” he admitted.

“We could fill it in with black,” I suggested.

“Next time.”

“Alright, lie down on the couch,” I said, preparing my tools.

“Ouch!” he exclaimed as I began. “I don’t remember it hurting this much during my first tattoo.”

“It did. As usual.”

“And it still does. Do people often ask for breaks?”

“Apart from you? Never.”

“Ouch!”

“It’s done. Stand by the wall so I can take a picture.”

“Not this time. I don’t like my back.”

“Come on, we always take great pictures.”

“Please, respect my wish.”

“Of course. I’m sorry.”

“I still have some time before my doctor’s appointment. How about a coffee?”

“With pleasure. But let’s go to a restaurant—I’m hungry.”

At Pois Chic, I couldn’t contain my excitement. “Oh my god, you have to try this couscous with ratatouille!” The dish, served in a clay pot, was perfection. “I’m so sorry you had tasteless couscous while I’m having the best couscous ever.”

Pierre grabbed a spoon and sampled it. “It’s properly cooked, indeed.”

“What’s your doctor’s visit about?”

“I need new antidepressants. The last ones left me completely numb. By the way, I should leave soon to avoid being late. I’ll pay for your lunch.”

“Please don’t.”

“I insist.”

As he stood to go, I asked, “Every time we meet for a tattoo, I ask you the same question: What makes you happy? And you always give a different answer. What is it now?”

He stared at the table for a moment before replying. “Happiness starts with wanting to do something. Being happy is the opposite of being depressed.”

“Pierre,” I said, “with all my heart, I wish you to want things again and to overcome this depression as soon as possible.”

His eyes glistened with tears as he stood, pulling me into a tight embrace. His right hand gripped my left shoulder as though anchoring himself. Then he walked away. I remained seated for twenty minutes, motionless.