“What brought you to London?”

“I’ve always loved London. Every time I visited, I felt like it was where I belonged. Before, I lived in Milan, but I never felt at home there. I thought moving here would be the right choice for me, and it turned out to be. I moved 15 years ago.”

“I suppose you love dogs, given that you’re a dog walker. But Milan seems like a much better place for having a dog than London.”

“Really? I don’t think so.”

“I mean, there aren’t dog zones here like there are in Milan. You can find one in almost every neighborhood there.”

“When I lived in Milan, I didn’t walk dogs, so I can’t really say. But in Northern Italy, there’s nowhere you can let dogs roam freely.”

“Hm, I’ve seen dog zones even at gas stations in Northern Italy. The way people approach dogs there is so different—like they’re kids, not these scary animals that might bite you, as you sometimes find in Eastern Europe.”

“Really? I didn’t really like Milan. I always felt out of place. But, like I said, dog walking came after I moved here. It wasn’t planned. I’m actually a professional dietitian, and my whole family are doctors. When I first moved, I would just watch dogs outside all the time.”

“So, what exactly makes London your place?”

“It’s the energy here. I feel calm and grounded. In a lot of other places, I don’t feel that way. In my hometown, I always felt like an outsider, but here, I feel like I truly belong.”

“Where does that feeling come from?”

“It’s the language. I can express myself best in English, and in London, I feel like no one judges me for being different or for having a German accent.”

“What makes you different?”

“My hometown is very small, and I was always different because I came from Germany. I had to learn to speak differently. I came from Munich, where we speak ‘proper’ German, then I moved to Northern Italy, where people speak both German and Italian, but German is more of a dialect, and no one could understand me. So, language made me feel different—there was this barrier where I couldn’t understand people, and they couldn’t understand me.”

“But what if I told you that sometimes, it’s not about the language itself, but about the connection built on the intuitive understanding of each other? I mean, how many people speak English in London? But does that mean they all truly understand you?”

“Hm,” she paused. “I never really thought about it like that. When I was little, I had a friend with whom I spent two weeks on holiday, arm in arm, and we couldn’t communicate with words. So, yes, I guess it’s really about that connection. I’m not sure why language made me feel alien when I moved to Italy, but maybe it was because I didn’t want to move there. When I was three or four, I told my parents, ‘I’m never going to learn Italian. As soon as I turn 18, I’m leaving and going back to Germany.’”

“Was there anything else that made you feel different?”

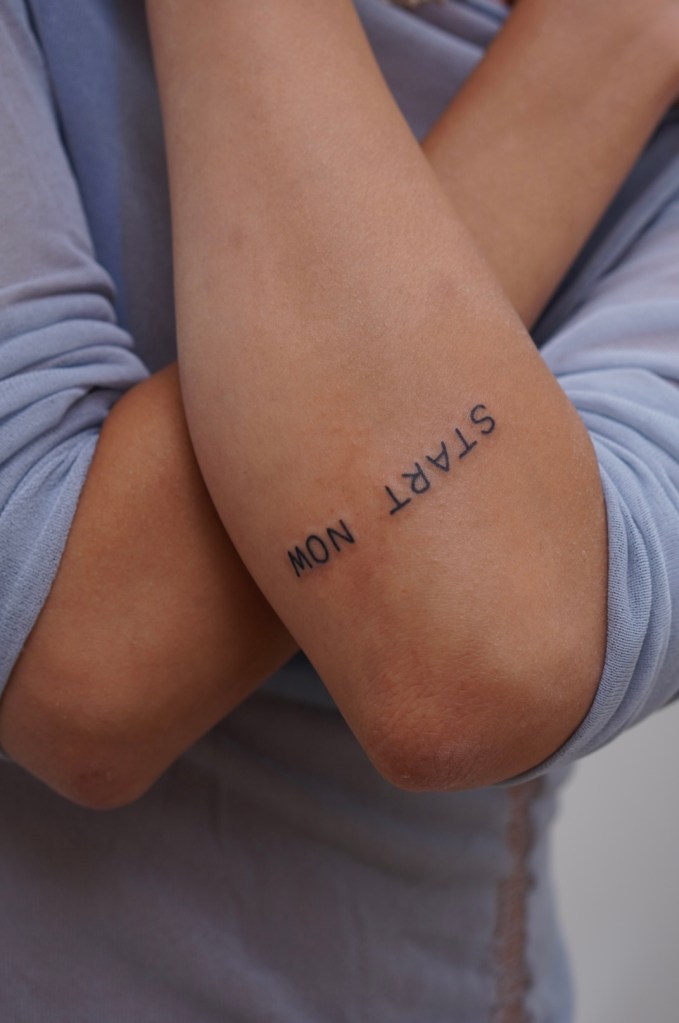

“The things I wanted were different from what others wanted. In my 20s, I tried so hard to fit in. But when I moved here, I suddenly realized I didn’t have to. I could be more myself.”

“How is it possible to be more or less yourself?”

“Maybe because I stopped doing the job my family expected me to do—the dietitian. They thought, ‘You went to university, you have to do something proper, not walk dogs.’ People thought I was odd, but dog walking is actually really important for my mental health. It lets me be outside, move around all day, and be with animals.”

“What happens in the evenings?”

“Evenings are… either very lazy or very active for me. If I stay at home, I tend to procrastinate—watching TV, eating, or I go out with friends.”

“But then, when you come back from seeing friends, what happens next?”

“It’s difficult.”

“Why?”

“I get really caught up in my thoughts. I got divorced last year after being with my partner for 24 years. So… that was a huge change.” She started to cry. “Sorry.”

“Does it still hurt?”

“Normally, no.”

“Does it hurt now?”

She paused, sighed. “It’s not so much pain as exhaustion.”

“Exhaustion from what?”

“From the whole process. I actually enjoy living alone now, and I love my life the way it is. It’s so much better than it used to be. It’s just… well, I had long Covid, then I found out about my husband’s affair. The divorce took two and a half years. Last week, I finally bought a flat, which also took half a year. It feels like I’m finally going to be… I don’t know what I’m going to be now—since all that is gone. Now, everything is great!” She laughed. “What am I supposed to do with this newfound calmness? Can I settle into it?”

“Were you expecting to feel relieved, rather than exhausted?

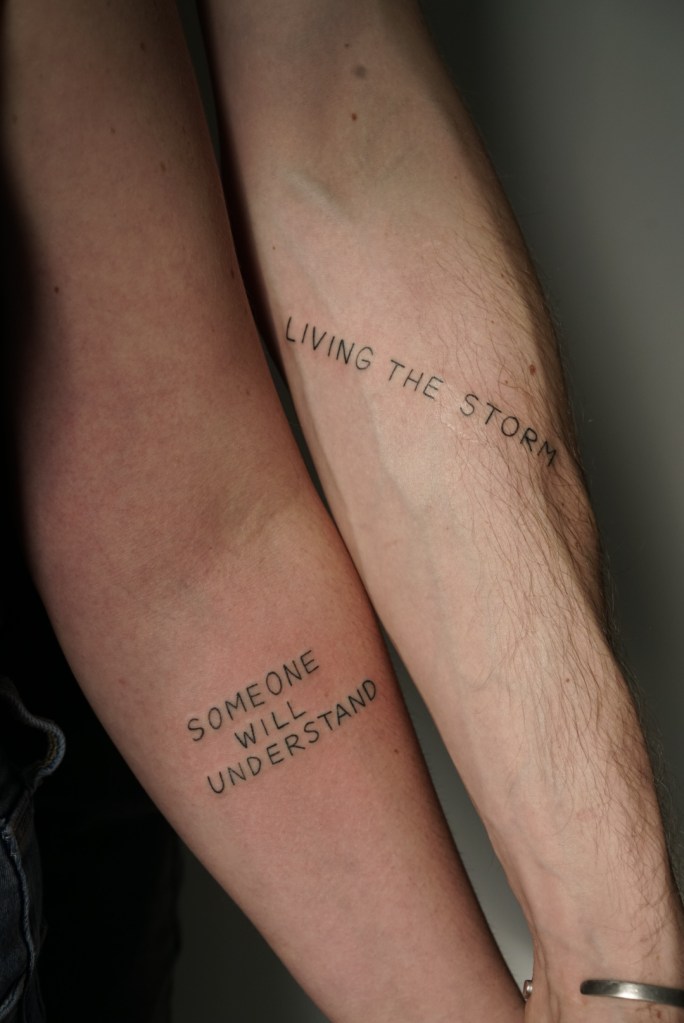

“Yeah, I thought the moment I got divorced, I’d feel ecstatic, free… but two weeks after, I just felt kind of…” She exhaled deeply, her tone heavy. “Like running a marathon, not knowing when the end is in sight. You push yourself, keep going, then suddenly you’re there, and all that built-up energy just drops off. It’s like the energy you’ve been carrying turns into a slump.”

“Could it be related to something else? Maybe, even if your life were perfectly stable, you’d still experience ups and downs? Perhaps the slump wasn’t just because of the divorce, but because of something like the lunar cycle, or a heavy meal that day, or poor sleep?”

“I’m sure that’s part of it. My mood has never been stable, and I’m aware that I’m going to experience those swings. But I think the external factors just don’t feel as threatening anymore.”

“What does it feel like to be grounded?”

“It feels like safety, like calmness, like being at home. It’s about feeling at home in my own body. When my mind slows down, when I stop chasing something and just exist in the present moment.”

“Can’t you feel that in places other than London?”

“I don’t. I probably should be able to, since it’s more about something internal than external. But I can’t explain why certain places have such a different effect on me.”

“I feel that difference too, but I remind myself that it’s just surface level, a decoration. When I was on a plane, flying over the UK, I looked down and saw a big city. I wondered if it was London or not. It’s hard to tell from up there—if you don’t pay attention to the details, all cities look the same.”

“I like how you called it ‘decoration.’ But for me, it’s also about the people.”

“Isn’t it true that people can be both nice and rude, no matter if they’re in London or Milan?”

“Yeah, that’s true. But here, I’ve made it work. I feel happy here. I love what I do. I like the people. I even like the weather. Even when it’s rainy, I’m cycling around. And I love the houses.”

“What’s that happiness?”

“It’s knowing I made the right choices.”

“And when you feel down, don’t you think the opposite? Like, you hate London?”

She laughed. “That would be really bad, considering I just bought a very expensive flat. Let’s not go there. No, when I’m in a bad mood, I try to think of it like bad weather—it will pass. But you’re right about one thing: I don’t know what’s coming next. There’s an old lovely man in the park, and every time he sees me, he says, ‘The only thing that doesn’t change in this life is change.’”

“What is your greatest fear?”

Tears welled up in her eyes. “Being lonely.” She struggled to speak. “I’m sorry.”

“It’s okay, don’t apologize.”

“I have a lot of friends, but with age and health issues, there’s a big chance my family will pass before me. That’s scary. And I don’t have children—I never wanted them—so… maybe I should get a dog?”

“What scares you about being lonely?”

“Since my divorce, I’ve become very close to my mum. She’s someone I talk to a lot. It’s not always easy, but she’s always there.”

“And what about the old man in the park?”

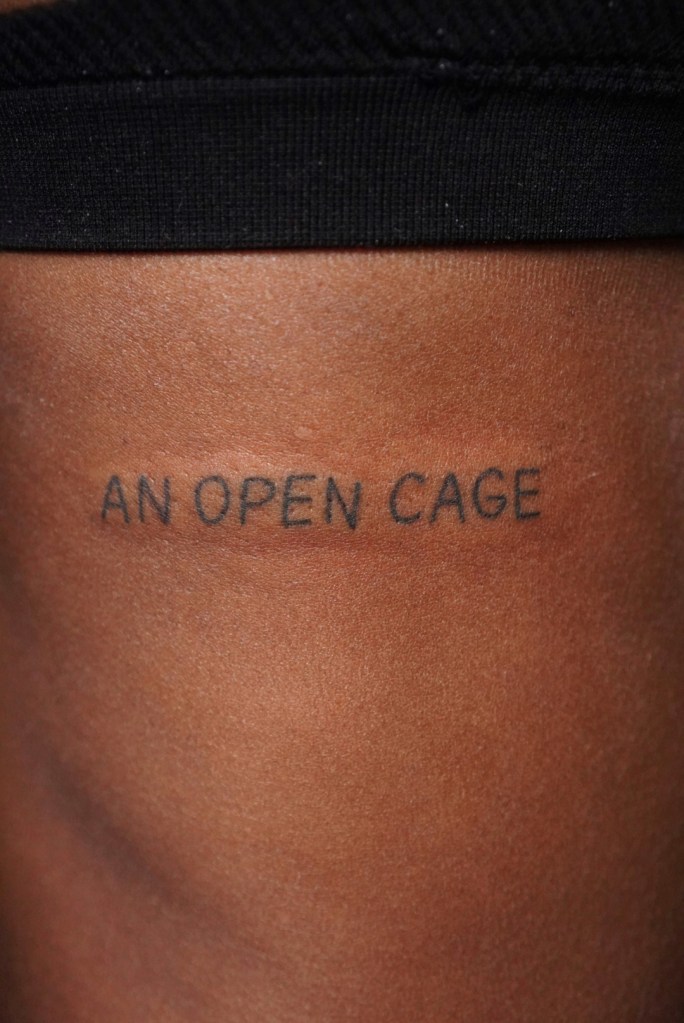

She laughed softly. “Yeah, my friends in the park—they’re always there for me. They’ve been a tremendous support. There are a lot of people around me, but sometimes I realize I’ve been lonely for a long time, even when I was married. I want to learn how to be happy alone. Right now, when I’m alone, I seek distractions. When I don’t go out, I quickly feel anxious—as if something’s missing, like I don’t exist without another person around.”

“I noticed I feel lonely when I’m tired or weak. So I investigated it, and I realized that in my vulnerable moments, I want to be with someone who can protect me, take care of me, while I recharge. Once I realized that, it became easier to let go of the loneliness because I’m not afraid of dying, so I don’t need anyone to protect me. Now, when I feel lonely or just tired, I know what to do: I rest. And then things get back to normal—I’m okay being alone.”

“And how do you rest?”

“I shut off all distractions and either go to bed or sit down to meditate. I try to do nothing as soon as I can, because if I wait too long, it becomes harder to rest, and then I end up with a sleepless night, which just makes the exhaustion worse.”

“I find it so hard to truly rest because I get almost paralyzed on the sofa, watching TV. It’s like I don’t let myself sleep because then my free time, my fun time, would be over. It doesn’t even make sense, though, because I waste so much energy bombarding my mind with TV and my phone.”

“I can only suggest not starting to watch TV or scroll through your phone. It might be easier than stopping once you’ve started.”

“Yeah. Another thing I know helps me a lot is exercise.”

“But you can’t exercise every time you feel lonely.”

She laughed. “No, I can’t.”

“And while exercise can distract you from your thoughts, it’s not really resting.”

“You’re right.”

“Are you familiar with the concept of ego elimination? If you put it simply, no ego equals no problems.”

“Do you think love is rooted in ego?”

“The desire to be loved—yes.”

“And loving someone?”

“I know of three types of love: unconditional love, reciprocal love, and selfish love.”

“Hm.”

“Reciprocal love is nice, but it’s not the greatest one.”

“Interesting. I hadn’t considered that. There are moments when it doesn’t matter to me, when I have this overwhelming feeling that love is infinite, that no love ever given is wasted. I can give, give, give—and never run out. But then with some people, I feel so selfish, like, ‘I’m not even asking you to love me back, but at least hold onto the love I’m giving you!’ It’s like, ‘Don’t love me back, but at least appreciate my love!’ Sometimes, I miss loving someone even if it’s miserable. I don’t know if it’s ego, but I want to feel like—‘Oh my god, I love everything about them, I see them, and I love them fully.’” She paused, then added, “I want to be seen for everything I am.”

“Why do you want to be seen?”

“To make it okay, to validate my existence. If someone sees me and doesn’t run away.”

“But you exist without needing validation. It’s not something you can discard.”

“I know, but it feels like I don’t exist if nobody sees me.”

“How many more times do you need to be seen to feel validated?”

“If I could just see myself, that would be enough.”

“Is there something you’ve always wanted in life but haven’t experienced?”

“I don’t think I’ve ever been truly loved.”

“What about your mum?”

She laughed. “Yes, she loves me, but I mean romantically. I want that burning love once in my life.”

“The way I see burning love is that it’s not something the other person gives you—it’s more about your own hormones getting all stirred up and you idealizing them.”

“I think now that if I don’t believe in love, or in big emotions, it’s because on one hand, I want all the calm, and on the other hand, I crave those big emotions.”

“What makes emotions ‘big’ for you?”

“I’ve always made safe choices in my life.”

“And now you want something more passionate?”

“Yeah. It’s even strange for me to go on dates. I’m in my mid-forties, and I’d never used dating apps until last year. They didn’t exist back then. The last time I dated was in ‘98. So now, I’m trying to figure out what I want.”

“And why do you need to want something?”

She laughed.

“I ask because I feel the same way. I often find myself wondering what to do with my life, feeling stuck, and then I think, ‘Why am I wasting time thinking about it? Whatever I think about, it’s already happening, and my life will unfold whether I want it to or not.’”

“I feel like I’m running out of time. And I can’t lie, I’m afraid of dying. It feels like I’ve missed out, like I haven’t fully lived. I feel like I’ve wasted so much time in this relationship.”

“Would you be ready to die after experiencing that passionate love you long for?”

“I don’t know. Sometimes I feel like I could stop wanting things, but then I get scared. I think, ‘I’m 45, if I stop now, I’ll be too old.’”

“Too old for what?”

“I don’t know! It just creeps up on me. My eyesight is getting really bad. I can’t see shit anymore. I have white hair now.”

“I don’t understand why that surprises you. You’ve been aging your entire life.”

“I know that, but when it becomes so obvious—especially when I look at my mum—it hits me that she won’t be around forever.” She began to cry.

“What makes you cry?”

“I lost my dad when I was 21. He died, and I miss him all the time.” Her laugh came through her tears. “Well, not all the time. That’s not true. It’s more like I have a missing part of me.”

“Would you want to stop missing him?”

“No. He made me feel really loved and seen. I miss that.”

“Earlier, you said you’ve never been truly loved romantically. But it seems like your desire for that comes from knowing the love you once received from your father. I’m not sure we can desire something we’ve never experienced. And, I see you, Pia.”

“If people still like me, love me, and don’t judge me when they see me…”

“Pia, I don’t judge you. Even though I’m a stranger to you, I love you.”

She was silent.

“Where I’m trying to lead you is to understand that if you can accept love from a stranger, then your problem is solved.”

She laughed. “So I can go ahead and die now?” She smiled. “And you’re right. I don’t need love from anyone specific. I don’t need it forever. Sometimes, even just walking past someone who smiles at me, and feeling like they see something in me—that makes me happy for hours.”

“I know that feeling. When I encounter a kind stranger, I suddenly feel so happy to live in a world…”

She cut in, “Exactly! In a world where you can just come across kind people! I love that! When I have a moment with a stranger on the train, on a bus, crossing a street, and we just look at each other and smile.”